|

back to articles

November 3, 2007

New York Times

Lowell Smith, 56, Dancer in Harlem Troupe, Dies

By Douglas Martin

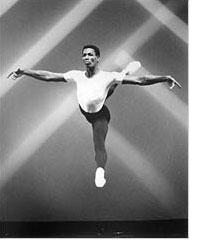

Lowell Smith, a principal dancer for the Dance Theater of Harlem who used precise mastery of classical ballet and exquisite expressiveness of body and face to convey emotions from tranquility to charged passion, died on Oct. 22, in Los Angeles. He was 56.

The cause was lung cancer, said Arthur Mitchell, a founder of the Dance Theater of Harlem. The cause was lung cancer, said Arthur Mitchell, a founder of the Dance Theater of Harlem.

Mr. Smith began at the dance theater in 1976, seven years after it was founded to give black dancers an entry into the white world of classical ballet. It began as a school, which still exists, and grew to international stature as an innovative and accomplished performance group. (The performances are now on hiatus for financial reasons.)

Mr. Smith, who spent 17 years with the company, developed a reputation as a powerful performer who stood out for his unusual combination of intensely dramatic performance and urbanity. He could thrust himself into a character, as he did as the tumultuous Stanley Kowalski in Valerie Bettis’s “Streetcar Named Desire,” or seemingly hold back at one remove, a skill he used to portray the quiet preacher in Agnes de Mille’s “Fall River Legend.”

Standing more than six feet tall, barrel-chested and projecting forcefully, Mr. Smith brought dramatic fervor to classical ballet. Moreover, in performances like “Streetcar” on PBS’s “Dance in America,” he successfully translated his larger-than-life characters to the smaller screen.

“He was the type of male classical dancer you don’t see anymore,” said Mr. Mitchell, who founded the Harlem with Karel Shook. “He had a presence.”

In Lester Horton’s “Beloved,” Mr. Smith played a religious fanatic who kills his sex-starved wife with muscular expressiveness and a glowering facial expression. As Dysart in “Equus: The Ballet,” by Domy Reiter-Soffer, his restless prowling gave movement deep psychological significance.

As Sharyar in Michel Fokine’s “Scheherazade,” he was a man of bearlike size and emotions who in the end seemed more wounded than those who died.

His performance as Stanley in the ballet adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s “Streetcar” drew perhaps the widest comment. Maggie Lewis, reviewing a Boston performance in 1983 in The Christian Science Monitor, called Mr. Smith’s Stanley “a beautiful mover who is also a bully.”

She continued: “You catch your breath as he struts and flexes in a taut trio with two card-playing buddies, but Smith keeps you on guard. He presents an intimidating character.”

Ballerinas appreciated Mr. Smith for his rocklike support, even as he made himself impossible to ignore. Virginia Johnson, the Harlem’s prima ballerina, said in a statement that Mr. Smith made her “feel 100 percent secure.” She added that “his powerful dramatic sense” pushed her “to find something to match it within myself.”

Mr. Smith was later director of the Kennedy Center Dance Project and the Dance Theater of Harlem School. Among the other places he taught were the Royal Ballet; the University of California, Los Angeles; Brown University; and the New York City and Los Angeles school systems.

Lowell Dennis Smith, the son of Gene and Dorothy Smith, was born on June 5, 1951, and grew up in Memphis. He first aspired to be an actor and attended the North Carolina School of the Arts, but switched to dancing and became principal dancer with Ballet South of Memphis. He said in an interview with The New York Times in 1982 that he preferred ballet to modern dance because “I hate rolling around on the floor.”

He elaborated on this thought while in Detroit in 1995 to teach ballet to children. “Ballet shows you there is an absolute right,” he said in an interview with The Detroit Free Press. “There is only one way.”

He arrived in New York as a scholarship student with the Joffrey Ballet, then performed with the Eglevsky Ballet. The New York Times in 1976 hailed his performance with the Eglevsky as an exotic visitor from Java in “The Nutcracker” as “sinuously rendered.” At 22, he joined the Dance Theater of Harlem.

In an interview with ABC in 1991, he said he had to push harder than he ever had to meet the artistic demands of Mr. Mitchell. Mr. Smith said, “I spent most of my time crying.”

He is survived by his mother, Dorothy S. Smith, and his sisters Pamela D. Smith and June Smith Floyd.

Mr. Smith said in his interview with The Free Press that what excited him about life were the things he did not know. One such revelation came when he first visited France with the Harlem group and discovered his favorite food: lamb’s brain salad.

|

|